- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

The part I found most important:

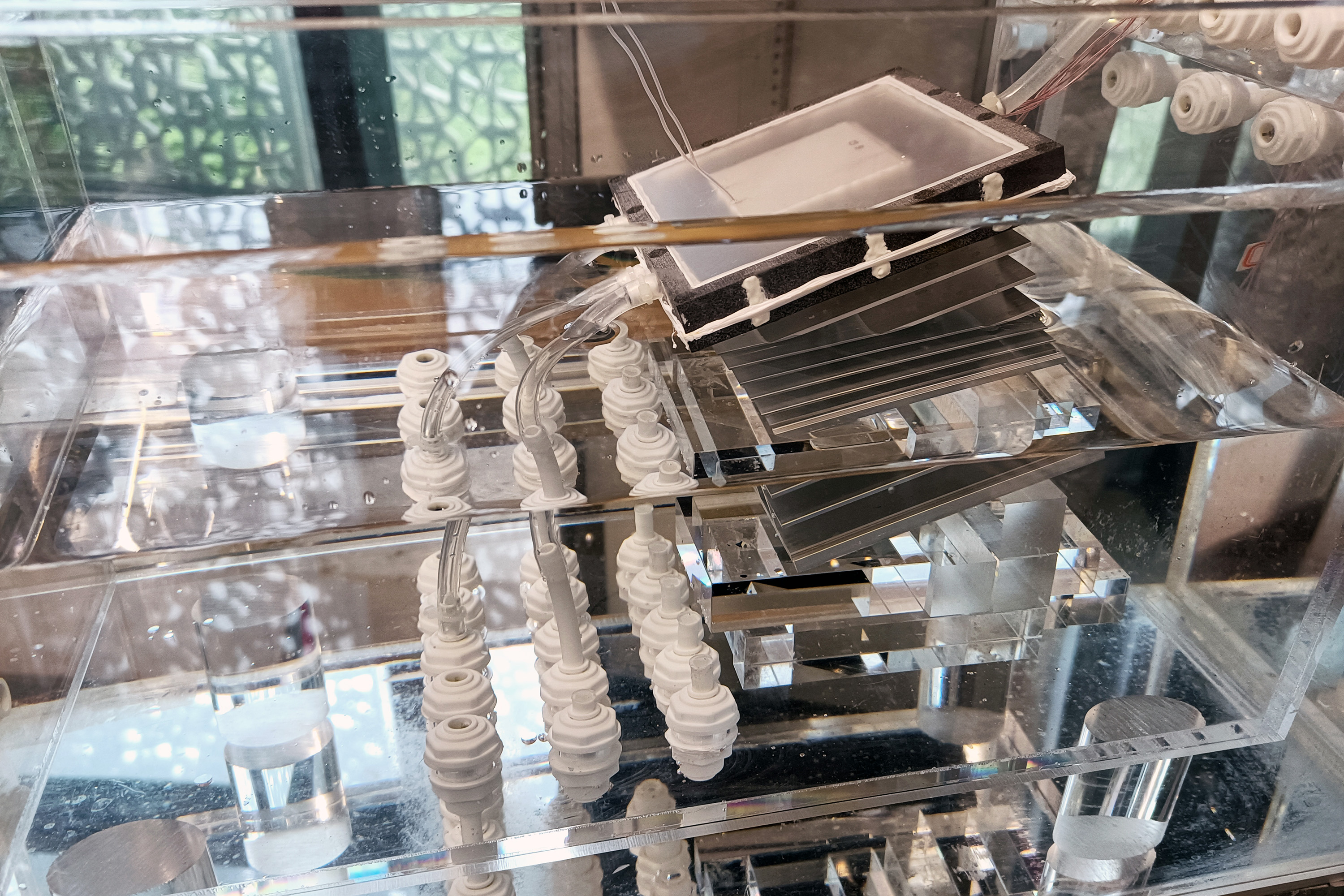

“The researchers estimate that if the system is scaled up to the size of a small suitcase, it could produce about 4 to 6 liters of drinking water per hour and last several years before requiring replacement parts. At this scale and performance, the system could produce drinking water at a rate and price that is cheaper than tap water.”

That could legit provide potable water for an entire house, with water to spare

If the parts are user-replaceable, that makes this invaluable for places like Polynesia where fresh water is becoming harder to acquire and people often live in remote small communities.

Doubt

This is great to hear. This tech is going to need to be near ubiquitous in a decade.

This showed up in my feed just above a post about New Orleans saying they need a freshwater pipeline because of saltwater incursion into the Mississippi. The juxtaposition was eerie.

It would be interesting to see what adding in some small external heat sources to augment the evaporation and allow it to run 24/7 would do to the cost/production values.

I never took fluid dynamics but would this disrupt the small eddies forming in this device? It sounded like the small/gentler eddies are the primary reason the salt is able to move and exit in a way that won’t clog the machine.

Possibly, but my take was that the solar heating is at the top of the device where the water/air comes into contact with the box walls. It sounded like they either use natural thermal convection or small devices to generate those currents. So the additional heat could make it run faster, or just trash the flows entirely.

But at the same tack, if you know how much heat is being added to the system by the sun, you could set your resistive heaters to only add that much and decouple it from needing solar to work (allowing production during night/inclement weather situations, or the ability to run inside in colder climates).

Don’t worry, some asshole will patent it and charge per bottle.

I was thinking that Bug Tap Water was gonna come in, sabotage the thing whilst claiming it’s bad for everyone, and then bring their prices up.

I know it’s just a typo, but I refuse to drink zee bugs!

A claim like that sorta sounds suspect.

Depending on how one gets their tapwater, it could be as simple as drilling a hole in the ground and getting the water, or putting a bunch of sand in a basin. The per liter cost of getting intermediate raw water from a slow sand filter is infinitesimal, pennies per cubic meter. Water from a slow sand filter must then be chlorinated for distribution, but so does water from a desalination plant because chlorination isn’t just for treating the water coming out of the tap, but it’s for protecting the water as it goes through water lines.

We are so fucked. Mother fuckers can’t use their brain for two seconds. What ya gonna do with all the salt. Power is only a little bit of limiting factor of desalination plants

One of the challenging issues with a complex problem is that the problem is not solved until the whole thing is solved.

One of the nice things about a complex problem is that you don’t have to solve the whole thing at once in order to make progress toward a complete solution.

I don’t know the state of the art on dealing with waste brine. If that is already deemed insoluble above a certain scale, then we better not invest in anything that exceeds that scale. On the other hand, if research into handling waste brine in sustainable ways is ongoing and making progress, then why not continue attacking the extraction problem?

I mean if the water is being used for drinking then put the brine into the treatment plant outfall so that it matches the salinity of the body of water it’s being discharge into…

It’s not quite that simple. After extracting water, matching salinity would require extracting salt or adding water. It’s not that there aren’t sources of water that can be used for salinity matching, including the output of sewage treatment, the reality is that it probably makes more sense to treat that water than to desalinate in the first place.

Extracting the salts might be a source of valuable minerals and metals, but there is still no free lunch.

As far as I know, we still would be putting stuff back that doesn’t make a good match for what we took. That means depending on the natural environment for dilution and “treatment”. That has been an ongoing problem for humanity. We’re very good at exceeding the capacity of the environment to cope with our wastes.

I completely understand the comment about perpetual motion machines, but tend to think that it’s more of a scale management problem than a strict prohibition.

I live in Vancouver BC, our drinking water comes essentially from mountain run off and snow melt in two local watersheds. We get less and less every year.

My thought is that with distillation we could use brackish/ river water, then concentrate the brine until it’s as salty as ocean water and put it in the ocean.

My thought about sewer outfalls was that adding the brine to the sewer flow should pretty much match the salinity of the source because any volume that goes into the pipes comes out of the sewers. (minus some evaporation).

As long as nobody is using drinking water for irrigation, the output does pretty closely match the input.

But my point was that we can treat that water for use and reuse. That way, the desalination is kept to a minimum.

Hey a perpetual motion machine violates the laws of physics. But why let that stop me from designing a power plant that uses one. One day will fix those pesky physics laws.

The impossibility of perpetual motion is not a reason to shut down research into methods of making power production and power consumption more efficient.

Are you saying that dealing with the waste brine is impossible in any way, shape, or form and that this is a reason to not pursue desalination research?

I used to be municipal water treatment plant operator (Level 2). I’m well aware that treatment waste is something that must be dealt with in any plant that does more than just disinfection.

I already admitted to not being up on the state of the art, but I was under the impression that there are potentially viable methods of dealing with waste brine in environmentally sustainable ways. Perhaps not at a scale that allows literally every human to use desalination for all needs, but that there are cases where desalination is a good solution.

My curiosity has been piqued. I will, of course, start looking for resources on waste brine management, but any pointers you have will be much appreciated.

Put it on french fries in the summer, and the roads in the winter.

Edit: This was a joke guys

It’s not nice and neat table salt. It usually comes to the form of an extremely toxic saline sludge. With who knows what other ingredients inside of it. It’s a major problem with this kind of thing. If you use it on an industrial scale a scale large enough to provide water for a city for instance, then you’re going to have enough output that will probably destroy whatever water source you’re extracting water from. Better hope no one fishes in that ocean, cuz they all going to die.

the roads in the winter.

Great fucking idea. Totally has zero issues with runoff. No one’s looking for an alternative because salting the road is so fucking awesome

You have good points, but why so rude? Especially since as @[email protected] showed that while they might be reasonable concerns, doesn’t mean there’s no solution for that, or that no one would think of that.

Because this kind of thinking is dangerous. It pulls attention and funding away from real solutions like water usage efficiency and reclamation

These plans are all so dumb. Where indeed does the salt go?

Back in the ocean, raising local salinity?

Uh, just make a mountain of it? Somewhere, somehow?

Poison the land. Poison the sea. Pick one.