After he found that formula for accurately and fairly assessing the impact an engineer makes, he should do anti-gravity next. Should be easy by comparison.

I was kinda baffled by this too. I like the general idea that they present (you need to pay your own long-tenured engineers higher than market rate cause they actually know more about your own system), but this idea of a formula? What, are you gonna start counting git commits? A formula sounds like a super weird way to solve that problem.

Just look at the engineers that add value in your company and pay them a fair market rate. When someone leaves, find out what salary they get in the new job and ensure all your remaining engineers get at least that amount and adjust as you go along. Something like that perhaps.

Sometimes your longest serving engineers can be your biggest anchor. Good engineers are (justifyably) highly opinionated about what can be done, but sometimes it turns into “what I do works, so all other ways are wrong”. At that point the best move for them might be to go learn how somebody else does it. Wish them well, and back a different horse.

Though in reality, management will push back any unorthodox approaches/solutions/approaches as risk and additional losses on R&D.

The hard part is “that add value”. Not only it’s hard to measure, but highly depends on scope of what is done

Counting commits is exactly the type of stuff starting to happen. linearb.io for example. I’m seeing this used as a way to rank dev value under the guise of “we’re just trying to help teams improve throughput”

edit: corrected url

Let’s do FTL travel directly after

…he should do anti-gravity next.

There’s a python library for that.

This one is very obvious. It’s not specific to the tech world. Companies know that changing jobs is stressful, that there’s value in remaining where you are, and quite obviously many people are willing to accept smaller raises so that they don’t have to go out and apply. For most jobs in the world, you can’t work remotely, and renting a different place or selling and buying property is time consuming, stressful, and expensive. In other words, this is common sense economic reasoning.

One side point is that if you can work mostly or entirely from home, that gets rid of some of the pressure to stay where you are, which in turn should create more mobility, which in turn should create more pay raises for employees who stay. But work from home is relatively the recent phenomenon, so old company pay scales are unlikely to properly account for it.

Another point, that the author completely overlooks, is that some people don’t contribute as much as the author thinks they contribute. If they know that, of course they don’t want to move to a place that does contribution-based pay. They could get hired on somewhere during a probational period of some kind, and their new bosses might think they’re not good enough, and now they are out two jobs. Of course the turnover on their second job makes their resume look weaker, so they’ll have more trouble finding a decent third job.

None of what I wrote is new information. It seems like the author of the article did that standard thing in tech circles. They decided to reinvent the wheel and write about it, and try to make it exciting when it’s not. Good for them for examining the problem, but they should be slightly embarrassed for publishing before doing basic research to see if someone had already addressed the question at hand.

This whole writing seems to assume that productivity is a feature of an individual and not a feature of a team. That’s a wrong assumption. The fairest way to pay is same salary for the whole team.

This writing is also PR for some individual company.

And this writing is three years old, written before the current economic slump. Nowadays the market is not so busy, at least not where I live in.

assume that productivity is a feature of an individual and not a feature of a team. That’s a wrong assumption. The fairest way to pay is same salary for the whole team.

So much of what we do produces nothing, but prevents a lot. There is definitely a reason to pay for experience and seniority: it’s not so much about creating widgets faster but more about not making short-sighted decisions. And in dev work, we have a high chance of making bad decisions as we’re second-generation lost-boys.

Having said that, those individuals are out there for whom compensation starts competitive and ends just short of their value. It’s eye-opening to meet and talk with these people and, once you do, it will change your life having them in it.

Above a certain level of seniority (in the sense of real breadth and depth of experience rather than merely high count of work years) one’s increased productivity is mainly in making others more productive.

You can only be so productive at making code, but you can certainly make others more productive with better design of the software, better software architecture, properly designed (for productivity, bug reduction and future extensibility) libraries, adequate and suitably adjusted software development processes for the specifics of the business for which the software is being made, proper technical and requirements analysis well before time has been wasted in coding, mentorship, use of experience to foresee future needs and potential pitfalls at all levels (from requirements all the way through systems design and down to code making), and so on.

Don’t pay for that and then be surprised of just how much work turns out to have been wasted in doing the wrong things, how much trouble people have with integration, how many “unexpected” things delay the deliveries, how fast your code base ages and how brittle it seems, how often whole applications and systems have to be rewritten, how much the software made mismatches the needs of the users, how mistrusting and even adversarial the developer-user relationship ends up being and so on.

From the outside it’s actually pretty easy to deduce (and also from having known people on the inside) how plenty of Tech companies (Google being a prime example) haven’t learned the lesson that there are more forms of value in the software development process than merely “works 14h/day, is young and intelligent (but clearly not wise)”

I keep waiting for someone to come up with some kind of explanation for this that even sorta makes sense. No, as far as I can tell, companies just work this way.

Well, I’ll give it a shot.

Part of it is that they can’t know the point that someone is willing to stay vs leave, and they’re always optimizing for that point. Saving money is always the goal for expenses in a company.

Part of it is that they have a budget that they can’t exceed. Sometimes a person is overqualified for the job, and the job simply can’t afford them. Sometimes that person will stay far longer than they should, when they could get paid much better elsewhere, and sometimes they choose to move when they’re only slightly underpaid for their skills.

Part of it is that there is more to a job than money. Being comfortable, un-stressed, and generally happy is more important at some point than more money. The company tries to balance these things, as it’s often cheaper to relieve or prevent stress than pay someone to put up with it.

In the end, it’s super complicated, but all about money, on both sides.

I’ll bite, too. The reason the status quo allows systemic wage stagnation for existing employees is very simple. Historically, the vast majority of employees do not hop around!

Most people are not high performers and will settle for job security (or the illusion of) and sunk cost fallacy vs the opportunity of making 10-20% more money. Most people don’t build extensive networks, hate interviewing, and hate the pressure and uncertainty of having to establish themselves in a new company. Plus, once you have a mortgage or kids, you don’t have the time or energy to job hunt and interview, let alone the savings to cover lost income if the job transition fails.

Obviously this is a gamble for businesses, and can often turn out foolish for high-skilled and in demand roles — we’ve all seen many products stagnate and be destroyed by competition — but the status quo also means that corporations are literally structured — managerially, and financially — towards acquisition, so all of the data they capture to make decisions, and all of the decision makers, neglect the fact that their business is held together by the 10-30% of under appreciated, highly experienced staff.

It’s essentially the exact same reason companies offer the best deals to new customers, instead of rewarding loyalty. Most of the time the gamble pays off, and it’s ultimately more profitable to screw both your employees and customers!

To add to that last point, I worked for a company (at retail) that claimed to know that keeping customers was cheaper than getting new ones, and corporate even implemented a policy where the clerks on the floor had up to $100 to keep a customer happy. I never once saw that $100 used, and the one time I tried to keep a customer (who had just spent $3000) happy, management refused to let him return a crap $100 printer because he didn’t have the manual in the box. He had left it at home, and was glad to bring it in next time he was in. Nope. And that incident was within a week of implementing that system.

So even when a company understands that point, it’s still really hard to make good on it at the levels that it can matter.

It’s almost like corporations are incentivized to be greedy and parasitic, instead of investing in their customers and workforce? I call it vulture capitalism.

He said in the article:

When hiring someone new, companies are forced to play in the open market, competing for top talent. But internally, they create opaque and informationally asymmetric compensation structures designed to minimize growth for existing employees to save the company’s bottom line.

So yes, this is totally just how many (most) companies are run. I work in healthcare and have faced similar issues, where someone I hired as a new grad who accumulated 5 years of experience with me would be making $20K less than someone I just hired who had 5 years of experience somewhere else. I always had some words for anyone who tried to talk to me about retention rates

Think of it from the company’s point of view. If you’re hiring a new employee then the options for a good candidate are a) move jobs and work for you, b) move jobs and work for someone else. You’re competing with other companies.

If you’re reviewing an existing salary for a good employee their options are a) do nothing and accept the shitty raise, b) move jobs and work for someone else.

Moving jobs has significant cost for most people - it’s time consuming, stressful, might involve moving house, etc.

That downside gives employees who haven’t proven they are looking for a new job a significant negotiating disadvantage.

If you really want you can tell your boss you are actively looking for new jobs. That will increase your chances of getting a bigger raise, but of course it has other downsides so most people don’t do that.

There’s downsides to the companies, though. Interviewing new candidates takes money, and takes time away from people already on the team. If everyone is switching jobs to get a higher salary, then companies aren’t saving anything in the long run. They also have a major knowledge base walking out the door, and that’s hard to quantify.

It’s a false savings.

If I were to steel man this, it’d be cross-pollination. Old employees get set in their ways and tend to put up with the problems. They’ve simply integrated ways to work around problems in their workflow. New people bring in new ideas, and also point out how broken certain things are and then agitate for change.

This, I think, doesn’t totally sink the idea of the “company man” who sticks around for decades. It means there should be a healthy mix.

I am in tech and so far the only way to get a decent pay rise was to swap jobs. Every 3-4 years. At my last position, I got something like 3-4% pay rise, for the last 3 years, when the official inflation was more than 20%, while I am sure they have adapted their pricing accordingly.

Every time it is the same story and excuses. And it is really tiring.

TL;DR: The ol’ classic of short-sighted money saving.

Often the money if far more than the individual realises.

-

Depending on the country, there may be taxes or other benefits which rise to the same degree or more.

-

Members of the team or grade need to be paid amounts which are within some range so that everything is fair.

You may feel you’re worth more than the majority of others, but it’s rarely the truth.

A VP was brought in at the company I used to work for that claimed “I need to offer candidates substantial increases or else I won’t attract top talent”. He started hiring people at a significantly higher rate. (I left at this point) Soon, the other engineers found out and all hell broke loose. They demanded equal pay.

The company is currently in financial difficulties. The salary bill got too big. They’re now struggling to complete the projects underway because they’ve had to cut staff and the 40yo company is probably going to be swallowed up.

-

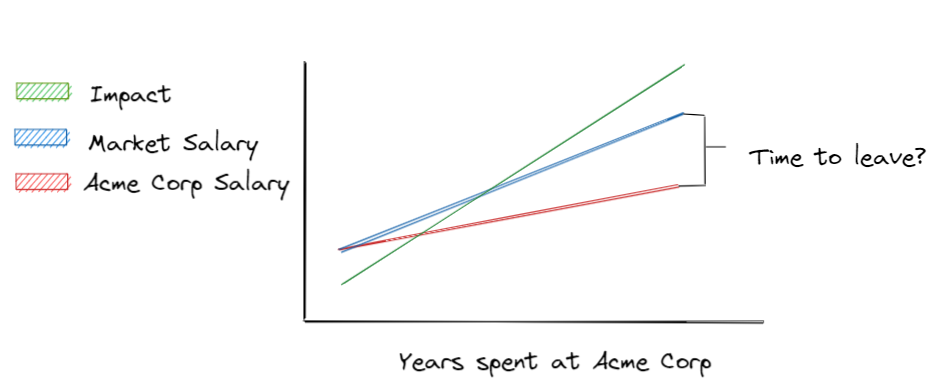

Companies try to maximize green per red. By paying less, and getting the same, they maximize that, year after year until (in a temporary and unforeseeable setback) you leave for… Bluer pastures, apparently.

There are different sorts of companies, and the more they think of employees as a number of years of experience plus a stack of skills, the more susceptible they are to believing that replacing humans with other equally skilled humans is a productive way to spend their time.

Some great comments here. Tangentially, I occasionally day dream of running or working for a company that flips typical corporate “intention” on its head – Specifically by placing employees at the highest place of priority and let profits, progress, customers, share price etc. be what they’ll be. I think that would be a very interesting experiment.

As far as how that relates to pay, part of the experiment would be to pay each employee more than they are “worth” to market. Just to see how it changes things for them and the company.

At the same time, “freeloaders” and folks that just can’t cut it would need to be identified and separated from, to protect those that recognize and appreciate that the company is truly looking out for them and are reciprocating with true hard work and value creation.